Benefits of protein for women’s hormones

Protein is a macronutrient and is essential for health. Amino acids are the building blocks of protein. There are 20 amino acids, 9 of which are essential, meaning the body can not make them and so they must be ingested through food. For women’s hormones in particular protein is essential to help aid the communication and effect of hormones throughout the body. In order for a hormone to do its job in the body, it must be accepted by multiple cell receptors all throughout the body, most cell receptors are proteins and thus they assist in helping all hormones perform their role. Protein is also essential for blood sugar balance, maintaining cellular structure and aiding in tissue repair. Protein is the building block of most of the hormones secreted by the pituitary gland eg. FSH, LH, TSH and prolactin. These hormones are peptide hormones that directly govern the release of our steroid hormones estrogen, testosterone and progesterone. Our pituitary hormones are responsible for making ovulation happen and without them, we can not make adequate hormones. A low protein diet has been linked with low growth hormone, low estrogen (and consequently low progesterone or lack of ovulation) autoimmunity and compromised thyroid function (1). Low protein diets are also associated with low prolactin levels during lactation which could interfere with breastmilk supply (2).

One of the most talked-about roles of protein in the hormone space is the huge role that protein plays in blood sugar balance, satiety and diminishing cravings. Protein, especially eaten at breakfast, decreases the hunger hormone “ghrelin” and increases hormones that help promote a feeling of satiety or the feeling of being full after a meal (3). Protein is also important in lowering the glucose load of a meal and has been shown to improve blood glucose response after a meal when compared to lower protein diets (4). Unbalanced blood sugar is often a root cause of many hormonal imbalances and is also greatly associated with mood and plays an important role in managing mental health disorders like anxiety. (read my blood sugar article here)

So how much protein is enough?

With all the essential roles of protein for women’s hormone health listed above it is easy to think that more protein is better, but this is not actually true. High protein diets can have a few negative consequences on women’s hormones. Higher protein diets based on a high intake of animal protein (as well as refined grains and high sugar foods) have been associated with high estrogen levels leading to estrogen dominance symptoms and an increased risk for developing breast cancer (5). It is also fairly well established in the research that higher protein intake, specifically animal protein which is devoid of fibre and also high in saturated fat has a negative impact on the gut microbiome (6). This leads to widespread inflammation which is a root cause of many hormonal imbalances as well as compromised immune function. This may also contribute to the re-circulation of estrogen in the body also leading to estrogen dominance symptoms (read my understanding estrogen dominance article here). Even when it comes to blood sugar balance, high protein diets have been shown to promote insulin resistance long term, increase blood sugar levels and actually increase the risk of metabolic diseases like diabetes (7)

It’s obvious from the research that too little protein is a problem but too much protein is also a problem for women’s hormones. So how much protein should women aim to consume? The truth is that the proportion of macronutrients needed in the diet is highly dependent on the individual woman and can change throughout the course of a woman’s life (eg more protein is needed in pregnancy or after menopause). As long as all macronutrients (protein, fats and carbohydrates) are accounted for in the diet in adequate amounts there is room to move with the amount of protein needed. Protein needs will differ based on a woman’s size, age, stress levels, activity levels, genetics and general lifestyle, however, as a general recommendation for women’s hormone health, we have studies suggesting adding about 20-30g of protein with each meal, three times a day aiming for a total of 60 – 100 g protein daily (8). At a minimum, women need 0.8g of protein per kg of body weight to avoid deficiency. For an average woman, this equals about 46g of protein per day. However, this is the minimum level required to avoid deficiency so most experts recommend aiming for about 1 – 1.3 g of protein per kg of body weight for optimal levels. Women living a very active lifestyle with lots of physical exercises should aim for the higher range. It’s important to remember that the amount of protein consumed is less important for hormone balance than the ratio of carbohydrates to protein. Eating a lot of protein may still not be enough to offset the negative effects of high carbohydrate foods like soft drinks and refined sugar-containing sweets and treats. In this case, it is much more beneficial to reduce the load of refined carbohydrates in general rather than trying to add more protein to compensate.

Does the type of protein matter for hormone balance?

There is quite a lot of information online about animal-based proteins being superior to plant-based protein sources for hormone health. The main reason for this is the idea that plant-based foods do not contain enough protein, are less “bioavailable” and do not contain all nine essential amino acids. It is true that animal foods have more protein than plant foods and that animal foods contain all the essential amino acids as well as many non-essential ones in a relatively evenly spread out way. It is however not true that plants are not complete proteins. All plants have all essential amino acids, but they have less of some amino acids than others. This is only a problem with a very limited diet where the protein source is the same, having a variety of plant protein sources covers all essential amino acids. Although the idea that animal protein is superior may sound convincing, the question worth considering is whether these ideas also correlate to positive health outcomes for women.

We have ample research now showing that animal protein is inflammatory (9) and that plant protein is anti-inflammatory (10). Inflammation is one of the largest underlying causes of many hormonal imbalances in women eg. PCOS, endometriosis, estrogen dominance, PMS and heavy painful periods. Although many experts claim that commercially-raised grain-fed meat is the reason that meat performs so poorly in all the health studies, organically-raised meat (although definitely preferable) still does not outperform plant-based protein sources in the research (10). As mentioned above, animal protein has negative consequences on gut health. This is why we have research demonstrating vegetarian women that naturally eat a higher fibre/plant protein-based diet have lower estrogen levels and excrete up to 3 times more unwanted estrogen in their stools (23).

Diets focused on plant-based protein sources show increased satiety and an increase of hunger-suppressing hormones (11). We also have extensive research showing improvements in blood sugar balance, insulin resistance and prevention of diabetes with plant-based diets (12) while a diet high in animal-based proteins and saturated fat worsens insulin resistance and is a known contributor to increased risk of diabetes (13). Similar results are obtained in women with PCOS where swapping out animal-based protein with a plant protein improved glucose control and insulin resistance (14).

Perhaps the most compelling study we have on protein on women and fertility/hormone health, shows that replacing animal protein with plant-based protein reduced the incidence of anovulatory infertility. This means that more ovulatory cycles are recorded when women replace animal protein with plant protein (15). This is important not only for fertility but for general hormone balance in reproductive years. This study was part of the large Nurses Health Study which is the most comprehensive study on diet and fertility we have (16).

Is animal protein more bioavailable?

The question of animal protein being more bioavailable is currently debatable. We have conflicting research in the area, especially for muscle gain, however, studies comparing whey protein powders with plant protein powders like soy, rice and pea have shown no difference in bioavailability (20) (21)(22). All plant foods contain all essential amino acids in varying amounts. All essential acids can be obtained through food pairing (eg rice and beans) and can be accounted for through the eating of a variety of plant foods throughout the day, in fact, amino acids do not need to be appropriately paired in one meal, as long as all essential amino acids are accounted in various foods throughout an entire day, this has shown to be adequate (19). Even for muscle gain, it appears that the total amount of protein is much more important than the type of protein (18) it of course much easier to reach protein requirements through eating animal products, but with a well-balanced plant prominent diet, you can achieve similar protein intake. Based on the best research we have, it appears that plant protein is preferable to animal protein for women’s health and fertility.

(*please note, exercise and muscle growth is not my area of research so have found the studies a little difficult to understand, there are definitely arguments on both sides based on what I can see in the research).

What are some of the best high protein foods to eat?

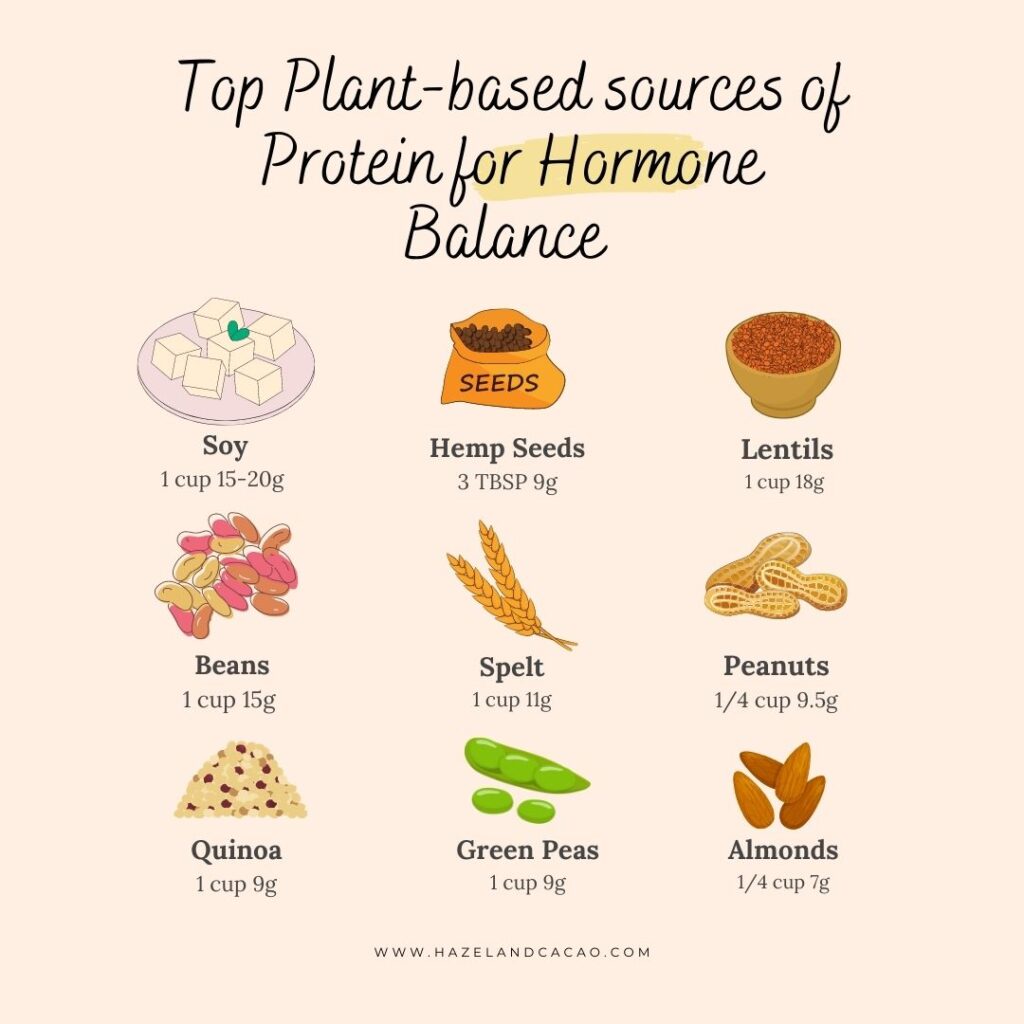

Plant-based protein sources include legumes likes chickpeas, various beans, lentils and soy in the form of tofu, tempeh, edamame, etc. Nuts and seeds are high in protein, in particular pumpkin seeds, hemp seeds and chia seeds as well as peanuts and almonds. Whole grains like quinoa, buckwheat and amaranth are high protein sources. Even vegetables like broccoli can have some protein.

If you do choose to consume animal-based proteins limit/eliminate processed meats and red meats as these have consistently performed worse in all health studies across the board. If there is no underlying intolerance or allergy, dairy is shown to be a preferred protein source to meat. Low toxin/low mercury fish such as salmon is also a preferable source of protein to other forms of meat. The science on eggs is debatable but in general, eggs also seem to be a preferred protein source to meat. Animal-based proteins should be a compliment to plant-based proteins and should not make the majority of the protein in one’s diet. However, because animal foods are a concentrated source of protein some women that have very high energy needs eg athletes may find it difficult to meet their needs without some animal protein in their diet. It is also very difficult for some women to transition to a plant-based diet due to underlying gut health issues and difficulty adjusting to the increased fibre needs. Although plant-based protein sources are preferable, a slow and sustainable move towards plant-based eating is advised for long term success in people with compromised gut health. A slow and sustainable move towards plant-based eating is also gentler on the system and gives the body time to adjust to making some of the proteins which it may not be accustomed to making anymore (when non-essential amino acids are consumed in excess from a young age, the body can downregulate its production of these amino acids as its getting them from animal products or supplements instead eg, creatine, it can take a long time before the body learns how to do this job again, so it’s better to be gentle on your body and go slow).

As you can tell from all the recipes on my blog, I do not eat any meat and have not done so for over 10 years. It was some of the research around animal protein and cancer that I read many years ago that convinced me to make the switch to a plant-based diet. It can be difficult to swallow the evidence around animal protein when so many societies have glorified animal protein as superior to plant protein for centuries. There is a sense of safety in “the way things have always been done” but the very large majority of dietary studies point to predominantly plant-based ways of eating for optimal health eg, Mediterranean diet, vegetarian diet, pescatarian diet, vegan diets etc. All of these diets can be done well when relying on mostly well-balanced whole foods and a wide variety of different plant foods.

References:

1.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5793233/

2.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005273615000516?via%3Dihub

3.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16469977/

4.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14522731/

5.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17455249/

6.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28215168/

7.https://www.nature.com/articles/ejcn2014123

8.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25926513/

9.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22426755/

10.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31037277/

11.https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/1/157

12.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5466941/

13.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2405457719303146

14.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29468748/

15.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3066040/

16.https://nurseshealthstudy.org/

17.https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/6/376

18.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31080071/

19.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3081312/

20.https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/11/3871

21.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30621129/

22.https://jissn.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12970-020-00394-1

This is so helpful! I’m curious – as an estrogen dominant person who is trying to move slowly towards plant based proteins – I’ve heard that soy can increase estrogen production. Have you come across this/would this be one option to avoid? Thank you!

I have a full article on my blog about soy phytoestrogens and hormones. Please read it if you can. In short, no this is misinformation. Soy acts as an adaptogen to women’s hormones and helps to balance estrogen depending on what the body needs. For women of reproductive age, soy is much more likely to lower estrogen.